In many ways, any venture into alternate history ultimately begins with something simple: a single bullet, a stopping heart, or—perhaps most famously—the flapping of a butterfly’s wings in some distant, unknown past.

Such elements have played key roles in the literatures of countless writers, especially since such similarly minor factors have repeatedly redirected history as we know it. The fate of the American Revolution, for example, might have ultimately been decided by a poker game. Before the Union victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, the American Civil War hinged on a piece of paper wrapped around three cigars, found in a field. A wrong turn in a stalling car resulted in the assassination that triggered World War I, whereas World War III was narrowly avoided in 1962 thanks to one little-known Soviet officer’s presence during the Cuban Missile Crisis. As for World War II, let’s not even get started on how different the world would be if a certain vagrant studied painting instead of antisemitism while in Vienna.

These are the turning points of history quietly lurking beneath the surface of the world we know, waiting to latch onto us and pull us down into an abyss of infinite possibilities. They mark a fine line between scholarship and speculation which even historians like David McCullough and Stephen E. Ambrose have delved into; perhaps to help us appreciate the history we have rather than fear the alternate routes we almost took. But how could such small footnotes ultimately affect the entire narrative of life on Earth? Is history so fragile that it both breaks and reconstructs itself with every touch? These are the riddles that authors of alternate history must confront after addressing the much more pressing question. The one that will ultimately decide their story: What if?

What if the Nazis won WWII? What if John F. Kennedy survived his assassination? What if the Confederacy won the American Civil War? What if Charles Lindbergh was elected president? What if a little-known politician died in a car crash? What if Hitler died in a movie theater? What if Nixon was elected to a third term? What if George Washington had been smothered in his sleep by his own powdered wig? Such possibilities have been explored in the respective imaginations of Philip K. Dick, Stephen King, Harry Turtledove, Philip Roth, Michael Chabon, Quentin Tarantino, Alan Moore, and… well, that incident with George Washington by the writers of Futurama. After all, nobody said alternate histories can’t be hilarious. Of course they can be!

This is what I have always found most appealing about alternate history—or, more specifically, counterfactual history, which uses scholarship and extensive research in order to effectively recreate these “What if?” moments in history. It is a tool used by historians in order to better appreciate the past, and when viewed alongside some of the freak occurrences that have repeatedly decided history, it’s impossible not to have a sense of humor about them. A poker game may have won the American Revolution? George Washington accidentally triggered the first “world war” because he didn’t speak French? The Second Battle of Britain was won because some scientist had a crazy dream? Thomas Paine miraculously missed his own execution because he slept with his door open? These are bizarre moments in history almost too far-fetched to work in fiction, but because they actually happened, they show the rewards that extensive research offers any realm of historical fiction.

Could this same approach be used to answer some of the sillier questions history offers? I say they can, and not simply because the above examples came from several Cracked articles I authored. I say this because, when I was an undergraduate, the chair of my history department routinely gave us assignments on counterfactual history, which he encouraged us to have fun with. After he retired, I asked this professor why he used such an unorthodox approach toward history, and his response was that as long as his students enjoyed themselves, he figured they would enjoy what they were studying even more.

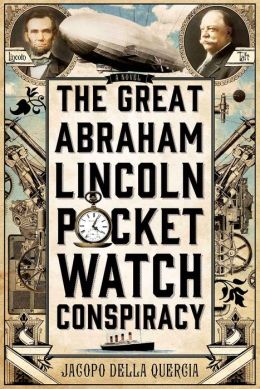

While I do not know if this approach works for every subject, I can safely say that it does with history. One of my essays for this professor took place within Abraham Lincoln’s mind during the last moments of his life at Ford’s Theatre. Ten years later, I reworked this essay into the prologue for The Great Abraham Lincoln Pocket Watch Conspiracy, which I wrote with the same attention to detail I would have given a master’s thesis. However, there was one massive departure between the scholarly approach and the one I took. Because my book was an alternate history, I was allowed even more creative freedom to establish people, places, and situations in rich historic detail than if I were writing a scholarly text. That’s right; by writing a fiction, I was paradoxically empowered in ways that ultimately made my world look and feel more real.

Such is just one example of the infinite possibilities alternate history has to offer. You can be as silly as Bill & Ted while educating readers as seriously as any scholar. You can take advantage of history’s innumerable, underexplored points-of-interest to shine the spotlight on fascinating—and hilariously named—historic figures like Major Archibald “Archie” Butt. (No joking, he has a fountain in front of the White House.) You can be as creative as you like, or you can take dictations from the actual historic record. There’s so much you can do with alternate history that it’s easy to become tangled in a web of infinite possibilities, and eventually becoming a stranger to your own reality.

The only advice I have to offer to readers and writers of alternate history is the same my professor offered: Have fun with it. Believe me, you have no idea where it will take you.

Jacopo della Quercia is an educator and history writer with several years experience teaching history at the college level. His debut novel, The Great Abraham Lincoln Pocket Watch Conspiracy, is available now from St Martin’s Press.